NIGERIA

“Giant

of Africa”

(A Brief History)

1.

Introduction

2.

History and Evolution

3.

The Atlantic Slave Trade

4.

Pre-Independence Nationalist

Movement

5.

Women in Nigeria

6.

Current Geopolitical Structure

7.

Conclusion

Introduction

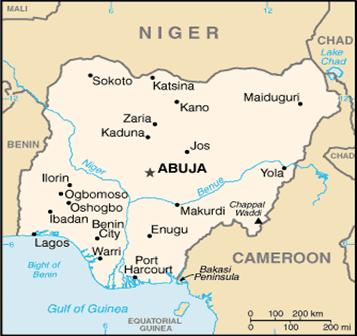

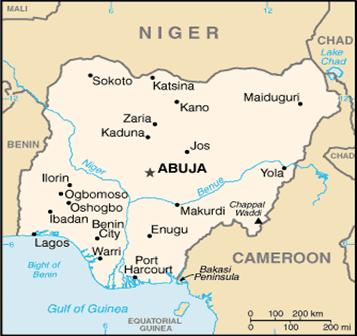

Nigeria,

with an estimated population of 126,635,626

is the largest black nation in the world.

The Federal Republic of Nigeria, as it is officially known, covers an

area of 356,669 square miles on the coast of West Africa. Its borders are contiguous with the Federal

Republic of Cameroon to the east, Niger

Republic to the north and Benin

Republic to the east. In the northeast, Nigeria

has a 54-mile long border with the Republic

of Chad, while its Gulf

of Guinea coastline stretches for

more than 500 miles from Badagry in the west to Calabar in the east, and

includes the Bights of Benin and Biafra. Today, Nigeria

is divided administratively into thirty-six states and the Federal Capital

Territory of Abuja (CIA World Factbook, 2001).

Like Africa

as a whole, Nigeria

is physically, ethnically, and culturally diverse. This is partly due to the fact that Nigeria

is today inhabited by a large number of tribal groups, according to the

Encyclopædia Britannica, an estimated 250 of them speaking over four hundred

languages, many with dialects. Muslims

and Christians comprise more than 80 percent of the population while the rest

are identified with indigenous religions.

However, Nigeria’s

greatest diversity is in its people.

These peoples have so much culture and history that it is imperative to

chronicle this history as it relates to their current economic and political

struggles. Dating back to the kingdoms

and empires of the early seventeenth century, from their involvements in the

Atlantic slave trade to its entire merger, this extensive history has blended

down to what is currently Nigeria

and is thus necessary in order to understand what has become of this once

fruitful and promising state.

Back to Top

History & Evolution

Nigeria only came

into being in its present form in the year 1914 when Sir Frederick Lugard, the

Royal governor of the protectorates, amalgamated the two protectorates of

Northern and Southern Nigeria. Sixteen

years earlier, Flora Shaw, who later married Lugard, first suggested in an

article for The Times that the several British Protectorates on the Niger

be known collectively as Nigeria

(Crowder, 21). Basically, the entire

Niger-area under British control became Nigeria.

It was in 1861 that the British

first annexed any part of Nigeria

as a colony, and attached it successively to West African Settlements,

including Sierra Leone

and the Gold Coast colony. The annexing

of Lagos, a coastal town and now

the largest city in Africa, led to the establishment of

a Southern protectorate in Nigeria,

and by 1906 both regions were united and designated a British colony. However, as Michael Crowder in his Story

of Nigeria states, “it would be an error to assume that the people of Nigeria

had little history before its final boundaries were negotiated by Britain,

France and Germany

at the turn of the twentieth century.”

In fact, the story of Nigeria

as it is known today goes back more than two thousand years. Within Nigeria’s

frontiers were a number of great kingdoms that had evolved complex systems of

government independent of contact with Europe. These included the kingdoms of Ife

and Benin,

whose art had become recognized as amongst the most accomplished in the world;

the Yoruba Empire of Oyo, which had once been the most powerful of the states

of the Guinea

coast. In the north, there were the

great kingdoms of Kanem-Borno, with a known history of more than a thousand

years; the Fulani empire which for the hundred years before its conquest by Britain

had ruled most of the savannah of Northern Nigeria. And finally, there were the city states of

the Niger Delta, which had grown in response to European demands for slaves and

later palm-oil; as well as the politically decentralized but culturally

homogenous Ibo peoples of the Eastern region and the small tribes of the

Plateau. All these state structures

grew tremendously through some form of trade, either internally or externally

with foreigners. One of the most

profitable of such trades being the trade with Europeans in humans, popularly

known as the Atlantic slave trade. Back to Top

The Atlantic Slave Trade

The major impact of Europeans on West Africa

was due to the Atlantic slave trade.

For the greater part of four centuries the trade dominated relations

between both the African and European peoples, and it continued to affect them

profoundly even when it was officially ended.

According to Crowder, Ewuare the Great may have been the first Oba

(king) of Benin

to meet a European (Crowder, 66). An

arrangement was made officially in 1472 when the Portuguese merchant Ruy do

Siqueira gained his majesty’s permission to trade for slaves, as well as gold

and ivory, within the borders of the Oba’s kingdom (Hines, 27). Contrary to speculations, the slave trade

was not a European innovation. Domestic

slavery was prevalent throughout the region, and many indigenous economies,

including those of the forest regions relied on some aspect of the slave trade,

whether it was collecting, marketing, or conveying the human cargo. Nevertheless, African participation in the

trade should not divert attention from the fact that the Atlantic slave trade

began with the arrival of Europeans, continued so long as the Europeans

required slave labor, and ended at European convenience.

In the sixteenth century, the demand

for slaves for the New World plantations had redirected

the slave trade from trans-Saharan trade routes to the coastal ports, and from

thence turned into the largest forced migration in history. Michael Crowder, who gave an extensive

account of the statistics in his Story of Nigeria, illustrated just how

cruel and depopulating this trade was:

Conservative estimates put the total number of slaves

exported from West Africa and Angola

as high as 24,000,000 of which probably only 15,000,000 survived the notorious

Middle Passage across the Atlantic. In the sixteenth

century about 1,000,000 slaves were transported to the Americas,

in the seventeenth century, some 3,000,000, and in the eighteenth century some

7,000,000 or 70,000 a year. Of these about 22,000 were shipped annually from

ports in Nigeria.

Benin and its

colony of Lagos sent about 4,000

and the ports of Bonny, New Calabar and Old Calabar, which grew up directly in

response to European demands for slaves, together with the Cameroons

sent some 18,000. Even in the nineteenth century, when many major European

powers had abolished slavery, and when the British Navy patrolled the coast of Africa,

another 4,000,000 slaves were taken across the Atlantic.

Many of these came from Yorubaland, where civil war produced thousands of

captives to be sold into slavery.

It

was also well noted that the men taken as slaves from the Nigerian coasts were

captives of war, or sometimes, like in the forest regions, were children sold

by their parents in the hope that they might find a more profitable life

elsewhere. For the Ibo, slavery was

said to have recommended itself as a relief from overpopulation and

insufficient land (Country Study Handbook).

It will be very interesting to find

out how the many Nigerians, who were forcibly settled in the New

World, fared. Well

basically, according to a country studies report published by the Federal

Research Division of the U.S Library of congress, most of them lost their

tribal identities, especially in those territories where families were broken

up indiscriminately and where no consideration was given to the welfare of the

slaves. It is noted also that this was

particularly difficult in the West Indies where common

participation was forbidden. However,

different tribes reacted differently to the new situation. The Yoruba, who were usually captured and

sold as a result of wars, were transported in large numbers, and many of them

found their way to Brazil and Trinidad where their masters were less oppressive

in attitudes thereby helping them maintain their culture. In fact, some religious ceremonies practiced

today in Brazil

can still be recognized by Yoruba from Nigeria. A further feature of this cultural exchange

between Nigeria

and Brazil was

the repatriation of large groups of slaves who revolted between 1807 and 1813. This also explains some of the European

surnames borne by some Yoruba and other coastal ethnic groups in Nigeria

today. The Ibo, on the other hand, were

not as organized as the Yoruba and were usually captured individually. It must also be pointed out that a large

number of slaves from Ibo territory were either already slaves or outcasts from

their own societies (Crowder, 77). Back to Top

Pre-Independence

Nationalist Movement

It should be remembered that no such

entity as “Nigeria”

existed until 1914. It was the creation

of a British government, which had seized control of its areas shortly after

the abolishment of the slave trade.

From then until October 1, 1960,

when she gained her independence, Nigeria

was under British colonial rule.

It was in 1807

that the British Parliament enacted legislation prohibiting the slave

trade. To enforce a blockade on the

Middle Passage, the Royal Navy detailed a squadron to patrolling the West

African coast stationed off the Niger Delta.

Though a lively slave trade continued until the 1860’s, it was gradually

replaced by other commodities, this shift in trade led to increasing British

intervention in the affairs of Yorubaland and the Niger Delta. Britain

granted a Royal Charter to the Niger Company in 1886 and gave it political

authority in the areas it controlled. By the end of the century their

commercial activities had extended British influence up the Niger

River to include the Muslim north (Arnold,

p. ix).

Since independence in 1960, the nation has struggled

and even fought to create a sense of nationalism. As an artificial creation involving such widely differing groups

of people, there have always been doubts as to whether Nigeria

can survive as a sovereign federation, a status it obtained in 1963. Prior to this started the Nigerian

Nationalist Movement, one in which Nigerians started to think of themselves,

much less as members of distinct ethnic groups but as citizens of one political

entity. It is said in many quarters

that Nigerian nationalism must have manifested itself right from the first

encounter between Europeans and the local inhabitants. Its goal initially was not self

determination, but rather increased participation in the governmental process

on a regional level. This movement

produced such prominent personalities as Herbert Macaulay, revered today as

‘the father of Nigerian Nationalism,’ and descendant of Bishop Crowther, a

freed slave. Also, there was Dr. Nnamdi

Azikiwe, President of the newly formed indigenous senate and eventually

Governor-General of the independent federation; Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Nigeria’s

first indigenous prime minister; and Chief Obafemi Awolowo, radical activist

and leader of the Action Group. The ideological inspiration for some of

these nationalists came from a variety of sources, including prominent

American-based activists such as Marcus Garvey and W. E. B. DuBois (Country

Study Handbook).

Back to Top

Women in Nigeria

On the contrary, the success of the nationalist

movement was not achieved by men alone, but by Nigerian women as well. The early stages of nationalist revolt

against entrenched British rule also took the form of local skirmishes like the

“Aba Women’s Riots.” In 1928 to 1930, Aba

women rose in protest against the oppressive rule of the colonial

government. These Ibo women of eastern Nigeria

feared that the head-count being carried out by the British was a prelude to

women being taxed. The women were

particularly unhappy about the over-taxation of their husbands and sons which

they felt was impoverishing them and leading to economic hardship. They also resented the British imposition on

the community of warrant chiefs, many of whom carried out what the women

considered to be abusive and extortionist actions. Their actions eventually forced the local chiefs to relinquish

their power, but not until after more than 50 women and an unknown number of

British troops and civilians were killed before authorities suppressed what is

today known as the Women’s War of Nigeria.

While they had less influence than men, women did control local trade

and specific crops, and they also protected their interests through assemblies.

Today, Nigeria

has many women’s organizations, most of them professional and social

clubs. However, the main organization

recognized as the voice of women on national issues is the National Council of

Women’s Societies (NCWS). Many of the

women’s groups were affiliated with NCWS, which tended to be elitist in

organization, membership and orientation.

In the 1980s, women from lower social strata in the towns, represented

mainly by the market women's associations, became militant and organized mass

protests and demonstrations in several states. Their major grievances ranged

from narrow concerns such as allocation of market stalls to broader issues such

as the standard of education of their children. As in other West African countries, women play a very important

role in family life in Nigeria

and this has given them the opportunity to branch out into various professions

and businesses. Back to Top

Current Geopolitical

Structure

Since independence, Nigeria

has experienced three republics, five coups and a civil war, not to mention a

severely battered economy. This,

amongst others, helped to shape the various geopolitical changes that Nigeria

has undergone since then.

Under the first republic, between

1963 and 1966, Nigeria was run with three administrative units that reflected

the three main geographical regions, the Northern Region of predominantly Hausa

and Fulani ethnic groups; the Western Region mainly Yoruba and the Eastern

Region of the Ibo. These ethnic

divisions partly led to the Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Biafran War,

which lasted from 1967 to 1970 and during which twelve states were

established. Three military regimes and

two coups later, the Second Republic

was underway but for a short period between 1979 and 1983. By this time, the number of states had

increased to nineteen. An additional

two states were created in 1987 and the Federal

Territory moved from Lagos

to Abuja officially in 1991. After two separate state creation exercises,

Nigeria now has

36 states and is currently in its Fourth republic.

The oil-rich Nigerian economy has

been long hobbled by political instability, corruption, and poor macroeconomic

management. Nigeria's

former military rulers failed to diversify the economy away from overdependence

on the capital-intensive oil sector. In

all, the military has held power for 29 years of the 42 years since

independence. Corruption is a very

serious problem in Nigeria

today and there is still much debate as to who has been more corrupt in the

past, the military or democratic politicians.

Civilians have also been blamed for mismanaging the economy and the

value of the Naira, Nigeria’s

local currency, has been steadily on a decline.

As one of the leading oil producers

in the world, Nigeria

has been a member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)

since 1971. The largely subsistence

agricultural sector has failed to keep up with rapid population growth, and Nigeria,

once a large net exporter of food, must now import food. However, more attention will have to be paid

to non-oil exports if any growth in the economy is to be sustainable. Nigeria

is also an active member of the U.N, the Commonwealth of Nations

and the Organization of African Unity, O.A.U.

It also stands as the headquarters for the Economic Community of West

African States (ECOWAS), the regional body of West African nations. Back to Top

Conclusion

President Olusegun Obasanjo, a former military ruler

before the Second Republic

but now a civilian, is presently the chief executive running the affairs of

this ever growing nation. He has been

faced with various challenges ever since assuming office in 1999 including that

of rebuilding an already tarnished economy, attracting foreign investment and

debt relief, and institutionalizing democracy by keeping the military in the

barracks.

Through a brief history of Nigeria,

it is very evident that Nigeria’s

strength in diversity might also be its undoing. Consequently, it is most

important that the Obasanjo administration defuses longstanding ethnic and

religious tensions, if it is to build a sound foundation for economic growth

and political stability.

For

Further Study

- Federal Research Division. Area Handbook Studies. 1991.

Nigeria:

A Country Study. U.S.

Library of Congress.

<

http://memory.loc.gov/frd/cs/ngtoc.html#ng0000>

- Crowder, Michael.

The Story of Nigeria, 4th Edition.

London:

Faber and Faber, 1978

- Arnold,

Guy. Modern Nigeria,

London: Longman, 1977.

- Hatch,

John Charles. Nigeria:

A History, London: Secker

& Warburg, 1971.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Nigeria"

<http://search.eb.com/eb/article?eu=120185>

- CIA – The World Fact book 2002. “Nigeria”

< http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/ni.html>

- The Women’s War in Nigeria

(1929 – 1930). December

16, 2000

<http://www.onwar.com/aced/data/whiskey/womens1929.htm>